Research says a lot about the importance of spelling as well as the connection between spelling and reading and writing.

Here are just a few research references about the importance of spelling:

‘The spelling to read movement spotlights the importance of spelling for orthographic mapping and spelling’s role in automatic word reading which drives reading comprehension.’

Why Spelling Instruction Should be Hot in 2022-2023, Psychology Today

‘The truth is that learning to read, write, and spell all help reinforce each other. Moreover, learning to spell enhances reading, writing, and literacy skills for young children in elementary school.’

How Spelling Affects Reading and Writing, IMSE Journal

‘The present study examined the possibility that spelling fulfils a self-teaching function in the acquisition of orthographic knowledge because, like decoding, it requires close attention to letter order and identity as well as to word-specific spelling–sound mapping.’

Spelling as a self-teaching mechanism in orthographic learning, Wiley Online Library

‘The author builds a partly theoretical, partly empirical case for the claim that learning to read and learning to spell are one and the same, almost. She concludes that they are one and the same because they depend on the same knowledge sources in memory: knowledge about the alphabetic system and knowledge about the spellings of specific words. She concludes that reading and spelling are not quite the same because the response performed to read words differs from the response performed to spell words. The act of reading involves one response, that of pronouncing a word. In contrast, the act of spelling involves multiple responses, that of writing several letters in the correct sequence.’

Learning to Read and Learning to Spell are One in the Same, Almost , APA PsychNet

With EBLI, our focus is on transferring this research to accurate, automatic spelling in the classroom (and beyond) in the most effective, efficient manner possible.

This blog is an overview of how we accelerate instruction and the companion Spelling and EBLI webinar will explore this topic more in-depth. The follow – up Spelling Workshop will provide you with applicable strategies and activities to improve spelling for learners of all ages and ability levels.

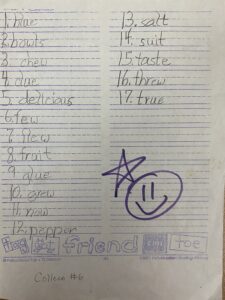

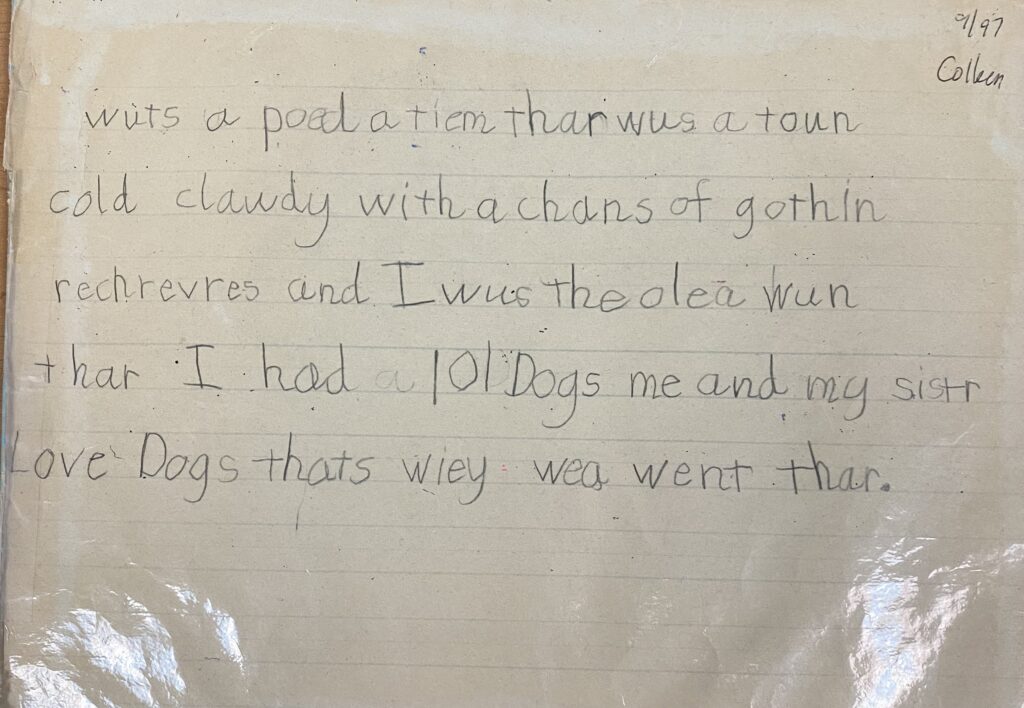

When my daughter, Colleen, was in 2nd grade in 1997, she appeared to be a great speller on spelling tests, but this did not transfer to spelling in writing, often misspelling the same words she’d previously spelled correctly on spelling tests. In some circumstances, she appeared to be an above average speller (and reader). In truth, she was below or well below grade level and her potential in both areas.

Here are examples of her 2nd grade work.

Colleen’s 2nd Grade Spelling Test

Colleen’s 2nd Grade Writing

Why was there such a significant discrepancy between her spelling on the test and spelling in her writing?

Spelling for a test is often an assessment of rote memory ability of strings of letters. We worked with her for hours every week to memorize those strings of letters and she held onto it until she regurgitated it for the test. Often she couldn’t spell those same words by the time she got home that afternoon. She did not have a strategy to spell.

Spelling requires accessing the sounds in words through segmenting and using the acceptable spellings for those sounds. Colleen had an idea of the sounds in words as she had been taught traditional phonics (Abeka) in Kindergarten. However, she had no idea how to spell them correctly but instead used her ‘Kindergarten spellings’ (the most common spelling for each sound) instead of the accurate spelling. In her writing, you see this by her spelling was as ‘wus’, there as ‘thar’, and called as ‘cold’. Even though she got some difficult words correct on her test (delicious…?!), she got very simple words incorrect in her writing.

With instruction based on sound first, Colleen learned to read very quickly. She was reading chapter books accurately after just hours of instruction. However, her spelling lagged behind reading, as is typical. For her, it was much more of a process to correct. It took about 2 years for her spelling to become consistently accurate in her writing. Because her spelling was corrected only at home and rarely at school, this was a more drawn out process. Research shows that seeing misspelled words results in decreased spelling ability. As Diane McGuinness laments in her book Early Reading Instruction, ‘Fix spelling! Seeing misspelled words results in worse spelling.’ (pg 117)

Teaching and correcting spelling not only benefits spelling but also benefits accurate word reading, comprehension, and writing. Quadruple the benefits! Hopefully, spelling instruction by sound and providing effective, efficient, student-involved corrections will soon become the norm.

Spelling is a code, and every code is reversible. Decoding, or reading the words, is receptive as the reader deciphers the word off the page. When explicitly taught how the English alphabetic code works, this is quickly done automatically and subconsciously through the process of orthographic mapping. Encoding, or spelling by writing letters that represent the sounds in words, is expressive. The learner is looking at a blank page and has to retrieve the correct or acceptable spelling. This is more difficult because it requires simultaneous processing (or doing several things at once) which increases the cognitive load or brain work. Also, there are many ways to spell almost every sound in English so knowledge of the code is needed. The more a learner accurately spells words in writing and accurately reads words in connected text, the more their brain will pick up the concepts and spelling patterns unique to English, and the more they will better recognize the correct spellings to use.

Improve spelling, and you will improve reading even faster! Accessing the sound, not the letter name, is key to accurate, automatic spelling. To spell (or read) ‘was’, whole word memorization is largely ineffective and letter names can cause confusion. Speech is natural so teaching both reading and spelling originating from spoken words speeds up all literacy instruction. In order to teach reading and spelling from spoken words, we must access the sounds then say the sounds as we write the spelling (letter(s)) that represents those sounds. When spelling starts from print or the letter name, we are leading with a man-made visual process that makes spelling, and reading, more complex and confusing.

Teaching spelling by sound can circumvent students making mistakes that result from using letter names and avoid extended periods of time misspelling words without corrective assistance. When a learner misreads or guesses words without corrective feedback, they become a chronic guesser and that habit takes a lot of instruction and support to reverse. The same is true when a learner misspells words without corrective feedback. It takes even more time to remediate and reverse the ineffective habit of inventive spelling.

Spelling is important. It is how we communicate with others when we are not able to speak to them. Poor spellers avoid writing and, when they do write, it is difficult for others to decipher their error-riddled text. Other areas of literacy are hindered too.

Teach your students or children how to spell by sound. Show them the correct spelling for errors and have THEM correct it. As with handwriting, spelling is a critical component of literacy. It needs and deserves explicit instruction and attention.

For a deeper dive into what was discussed here with examples shared to elaborate on the information shared, check out this Spelling and EBLI webinar. Also, as a new offering, I will be teaching an online workshop on the process to teach spelling words, correct spelling in writing, and strengthen weak areas in spelling for your class, intervention students, or children. Click here for more information.