How long should students continue reading decodable books? Do they need leveled books? When and how can they move to getting a book from the library or store, advancing to reading whatever they want?

The importance of reading in connected text is critical to improving reading. Of course, the reader must have a foundation in decoding instruction in order to read words accurately and automatically. Beginning readers as well as many, if not most, sub-literate learners have holes in their decoding repertoire.

Once the foundation is firm, which can happen quite quickly with a speech first, Say Spell Read, Speech to Print approach to instruction, expanding student’s supported and independent exposure to trade books and more complex text is critical to their further growth in reading.

Orthographic mapping, set for variability, statistical learning, and the self-teaching hypothesis all inform the importance of moving quickly to reading in text, supported and then independently, once a foundation of explicit instruction on decoding is in place.

Below are general explanations of the terms in the above paragraph. After you read them, you may be thinking…whaaat??? I certainly can relate! No need to worry; further along in the blog I will explain the terms in the perspective of how they are applied in reading instruction.

Orthographic Mapping

“Orthographic mapping is the process that all successful readers use to become fluent readers. Through orthographic mapping, students use the oral language processing part of their brain to map (connect) the sounds of words they already know (the phonemes) to the letters in a word (the spellings). They then permanently store the connected sounds and letters of words (along with their meaning) as instantly recognizable words, described as “sight vocabulary” or “sight words”.

The Role of Orthographic Mapping in Learning to Read, Keys to Literacy, 2020

Set for Variability

“Set for variability is seen as a process that “cleans up” this mismatch between orthography to phonology conversion and word pronunciation. For example, a young reader may decode wasp to rhyme with clasp, however upon recognizing that /wæsp/ is not a real word, she must then flexibly apply different pronunciations for the letter a to arrive at the word, which is in her listening vocabulary.”

The Role of Set for Variability in Irregular Word Reading: Word and Child Predictors in Typically Developing Readers and Students At-Risk for Reading Disabilities, NIH, National Library of Medicine, 2019

Statistical Learning

“Implicit methods that draw on the principles of SL (Statistical Learning) can supplement the much-needed explicit instruction that helps children learn to read. This synergy of methods has the potential to spark innovative practices in literacy instruction and remediation provided by educators and clinicians to support typical learners and those with developmental disabilities.”

Reading as Statistical Learning, ASHA WIRE, 2018

Self-Teaching Hypothesis

The self-teaching hypothesis, proposed by David Share, is the idea that once learners have established their knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondences and the essential process of segmenting and blending, they begin to apply this knowledge to new and novel words. Proficient decoders can do this because the reader is able to pay attention to the order and identity of letters and how they map onto the phonological representations, or spoken form of the word.

The Self Teaching Hypothesis, Five from Five

When it comes to choosing text for students to read, there is an abundance of discussion and perceptions around the types of books students can and should be reading. With EBLI, we accelerate the advancement of students into reading trade books, including students in Kindergarten. The research on the topics listed above supports this practice.

The anchor to make this possible is students having a sound foundation in matching sounds in words to the letter(s) that represent these sounds in print. This applies to both the basic and complex level of decoding. Basic level refers to deciphering words with 1 letter spellings representing sounds such as ‘hop’, ‘slip’, and ‘strap’. Complex level refers to words that contain spellings represented by 2, 3, and 4 letters such as she, high, and thought as well as most multi-syllable words such as funny, hurry, and neighbor.

There are two common types of instructional approaches, both of which have differing types of books for students to read that expand on what is being taught.

Traditional phonics instruction encourages the use of decodable text that utilizes only words using spellings that have been explicitly taught. For example, if the class/student has been explicitly taught s, t, a, n, p, and i, they would read books with these types of sentences: ‘Pat sat in a tin. Tim naps.’. This provides a lesson to text match though words to be used are limited. Often decodable text is used for several years of instruction.

Decodable book examples:

With EBLI, we solidly support using decodable books for the first several months of Kindergarten and for a small percentage of students initially who require remediation. However, because of the comprehensive, integrated, sounds-first instructional process used in EBLI, transitioning to reading trade books (books children get from the library or a bookstore) typically happens within weeks or, with emerging readers, sometimes months. Even when we do utilize decodable books, there is flexibility in using books with words that utilize spellings that have not yet been explicitly taught. See Marnie Ginsberg’s Is There a Third Way? webinar for insights and information on this speech-first, Say, Spell, Read, linguistic phonics approach.

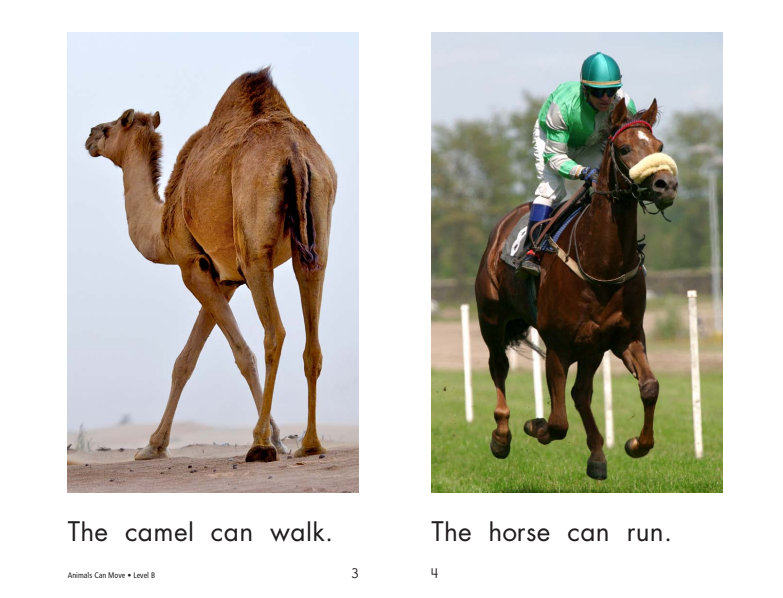

Balanced Literacy instruction advocates for the use of leveled books from the beginning of kindergarten and beyond. In the earliest levels, students are given books that contain a pattern that has a similar sentence structure and repeated words that are memorized, and requires relying on the picture to figure out the other words in the sentence. Because children at the beginning of Kindergarten would not know how to read camel, walk, or horse, they would require the picture cues or guessing as their main strategy to figure out what the words might be.

Level B example:

With EBLI, we strongly discourage the use of Levels A-D for beginning readers as they often result in students creating inefficient habits such as guessing and looking at the picture which lead to misreading. These habits are then difficult to reverse.

If students have been taught how to accurately decode words with simple and complex code, they are able to move to reading a wide variety of text. If leveled books (beyond level D) are available, books Level E or above can be used in supported and/or independent reading. The goal with EBLI is to move all children into trade books as quickly as possible. This prevents hindered learners by the limited word choice and vocabulary in decodable books. It circumvents students from being locked into levels that prevent them advancing and/ or from choosing text that they are interested in or want to read. Guessing, memorizing, or looking at pictures is avoided in all reading, regardless of the type of text.

When foundational instruction on deciphering the English Alphabetic code (decoding) is taught to students they have the foundation to be well on the road to accurate, automatic reading. It is at this point that implicit learning comes more into play.

Once a learner has had explicit instruction, this knowledge will expand through implicit learning. For example, if they’ve been explicitly taught beam and teach by matching the sounds in the words to the spellings, those words become orthographically mapped (they can read them automatically without needing to sound them out), they will use that information and apply it to other words with the same pattern such as treat, beach, and please.

With explicit instruction in phoneme manipulation (deleting a sound and replacing it with a different sound) and that the same spelling can represent many sounds: ea represents the sound /ee/ in team, /ai/ in great, /e/ in head, they will be able to implicitly apply this to other words and use set for variability to correct when a sound is misread in a word from their vocabulary. For example, if the word ‘great’ is read as ‘greet’ in a sentence such as ‘You are great’, they will have the skill and knowledge to remove the /ee/ sound and replace it with /ai/, possibly with support at first but typically without prompting.

Statistical learning takes place subconsciously, after and in conjunction with explicit instruction. As Mark Seidenberg says in his book Language at the Speed of Sight, “Explicit instruction and conscious effort are the visible tip of the iceberg; statistical learning is the mass below the surface.”(pg 87). When learners are provided with solid, explicit instruction that starts with speech and includes the skills and concepts unique to the code used for reading and spelling, students will automatically expand on this information through statistical learning and self-teaching. At this point, a significant decrease in explicit instruction is needed and instead, more reading in text is what will accelerate reading.

Thanks to the above researched facets on how the brain learns to read, students do not need to be confined to controlled text, either decodable or leveled, and the majority of their learning – expanding their phonological, phonic, vocabulary, morphology, and background knowledge – will happen ‘under the surface’ or intrinsically.

To hear expanded information on this topic and what it looks like to scaffold instruction that quickly leads to accurate, automatic reading in trade books, check out the Supported Reading in Text free companion webinar to this blog.