Trauma. Anxiety. Suffering.

These experiences are widespread and deeply embedded within most, if not all, of the children and adults who experience sub-literacy or illiteracy. Their teachers, parents, and loved ones commonly experience secondary trauma.

Trauma and anxiety around reading is a topic I’ve been wanting to write about, while at the same time have actively avoided, for a very long time; I feel nauseated as I type. Addressing this takes me back to 1997 when my own child was suffering because she hadn’t yet been taught to read.

Since then, the long, winding road navigating the tears, anger, anxiety, avoidance, and shame of the thousands of learners I’ve taught who think they are dumb, broken, and incapable of learning because of their prior failures is ever present in my mind. The winding road continues to grow longer every day. Teaching and supporting the frustrated, hardworking teachers is fraught with challenges. Comforting the crying, desperate parents is emotionally taxing. Being mindful to sidestep the minefields full of blaming and divisiveness surrounding the reading wars is exhausting.

But, this topic is too important for me to continue avoiding it, for the sake of everyone involved.

Going to school day after day, week after week, for years while being unable to read or read well is, in the words of Psychologist Steve Dykstra, frequent and repetitive trauma for the student.

At our reading center and in coaching EBLI teachers, the experience of dealing with trauma and fielding questions about addressing it are prevalent. The learners do not believe that we can teach them to read because they have almost all been told before that they would learn to read and were let down. In some cases, children and their parents have been told they will never learn to read.

When working with teachers, they are very skeptical that the training and instruction we provide them with will REALLY be effective and efficient. Every few years, teachers are yanked to a new program that is promised to be ‘the answer’, except it hasn’t been. Teachers are exhausted and frustrated with working tremendously hard and still ending up with many students who are sub-literate. They also get blamed, from all sides, when students don’t progress.

By the time students get to our center, parents have spent much emotional and physical energy as well as time and money to try to help their child, they are despondent and desperate. Many times they have been met by resistance from administrators and teachers at their child’s school, which leaves them feeling lost, overwhelmed, and often angry. They are cautiously hopeful while at the same time doubtful about the possibility of their child becoming a proficient reader.

We embrace the skepticism from all stakeholders. Every one of these groups SHOULD be skeptical. The only solution is to teach the children (or teachers) and have them experience for themselves what is possible. The most important factor for anyone who is interacting with those traumatized in this arena is always, always the same: coming from a place of respect, grace, patience, kindness, and authenticity. This is easier said than done in some circumstances, but if the student – or parent or teacher – does not feel safe, then this compounds the trauma and limits the learning or progress.

These books and videos will give tremendous insight into what the suffering of sub-literate children, who then become sub-literate adults, experience. Each one of them is powerful but not comfortable to read or listen to:

The Most Unlikely to Succeed by Nelson Lauver

Nelson is a nationally syndicated radio broadcaster and learned to read at 29. I taught him EBLI when he was 50.

This video is about his experience (there are a few technical glitches in the middle of it).

The Teacher Who Couldn’t Read by John Corcoran

This book of John’s was the one that really opened my eyes to the excruciating experiences from the student’s perspective.

David Chalk, Learned to read at 62

David’s EBLI instruction was filmed for The Truth About Reading documentary.

Follow up interviews with David

It was hell…life before learning to read at age 62.

Emerging from hell: A year after learning to read.

I’m Free!

What can we do about this? Here are some of the ways we help students – as well as teachers and parents – feel safe:

Create trust

Provide very clear expectations at the beginning.

Ex: ‘We are going to work for 30 minutes with you following my directions and avoiding side conversations, drawing on the board, fiddling with items on the table, getting out of your chair (whatever behaviors sidetrack instruction).’

Spell out the consequences for reaching or not reaching the expectations.

Staying on track will save time so you will have an opportunity for free time to draw on the board at the end (or some small reward).

If I have to give more than two reminders about staying on track, we will have to try again for free time next time.

Follow through with what you say you will do.

If you promise free time at the end of the lesson for staying on task, be sure to give it if it is earned and don’t give it if it isn’t.

Be honest and transparent.

Some phrases to try:

‘I understand you don’t believe me and that’s ok. I can see why you wouldn’t.’

‘If you have any questions about anything I’m saying/teaching you please ask and I’ll do my best to answer. If I don’t know the answer, I will tell you that and then look to find the answer.’

For parents and teachers, offer them resources and contact information to others who were at one time in their situation. Stories that are relatable, from people who started with skepticism and had a positive outcome, help decrease anxiety.

Acknowledge their feelings (and yours)

I notice you seem angry and that is understandable. Do you want to talk about it?

I’m sad that you are suffering and I will help you.

Be respectful

Use their name in conversations.

Give choices – ‘Do you want to read first or later in the session?’

Recognize their behavior but avoid labeling it – or them – as bad.

Examples:

‘I notice you are telling me stories when the work gets more challenging. We are going to stay on task and you can tell me a story at the end.’

‘When you lay your head on the table, it is difficult for oxygen to get to your brain so it is important for you to keep your head up.’

‘Drawing on the whiteboard distracts you from learning. I will hold your marker until you need to use it.’

Manage panic around reading in books or other connected text

Start with text that has a larger font size.

At first, start with a small amount of text on a page.

Jokes are good for this.

Poems work well (Shel Silverstein is one of our favorite go-tos)

Cover up everything below the first line of text as you read.

Write the first sentence on the board, support the student as they read, then show them the same sentence in a book and have them reread it there.

Emotional release often leads to a breakthrough

Those who struggle with reading usually have a powder keg of emotions bottled up inside.

With reading instruction, especially when expected to read and/or when they make errors and get corrections, these emotions often come pouring out.

When a learner cries, acknowledge their feelings and provide them space to let them out without talking or judgment.

We have learners take a moment, go to the bathroom and splash water on their face, then come back and do some additional instruction (we rarely end the session directly following an emotional release).

This is important, even if it is for a few minutes of instruction.

Doing this allows them to end on a positive note.

An emotional release almost always is a breakthrough and resistance diminishes tremendously.

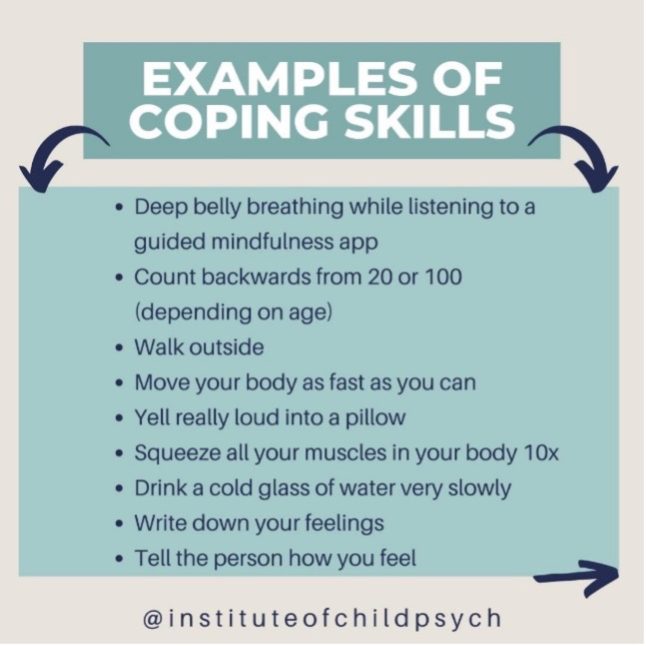

Provide opportunity to manage anxiety

Give a break and do deep breathing or other focusing activities for a few minutes.

We find Brain Gym’s Hook Up exercise (#5) to be beneficial.

Here are some other suggestions from the Institute of Child Psychology:

The bottom line is that effectively and efficiently teaching a child to read can alleviate the trauma and anxiety that have accumulated over years of reading struggle and failure, or prevent the trauma from happening in the first place. Check out our Alleviating Trauma and Anxiety around Literacy webinar for elaboration on what was shared in this blog and see some practical applications.

Dr. Steven Dykstra has many excellent presentations about trauma. The following quotes from one of his articles are a perfect ending to convey the power that effectively teaching reading has on a learner:

“Don Meichenbaum, one of the world’s leading experts on trauma and violence, and one of the most influential mental health professionals of the last century, said one thing is more important to traumatized children than anything else. More important than therapy, more important than social programs, more important than anything else. The research shows that the single most powerful predictor of their ability to overcome the trauma and survive their circumstances is the ability to read. If they can read, they have a chance to find success in school and overcome all those terrible things in their lives. If they can’t, school will only be another source of pain and failure added to all the other sources of pain and failure. If they can read, they can benefit from therapy and everything else we may try to do for them. If they can’t read, all of that is a waste of time.”

And this about severely traumatized children:

“Do what you can to clothe and comfort them, but know it will never be enough. You will not save them. Instead, understand that teaching them, and especially teaching them to read is the salvation you have to offer and the salvation they most need. Don’t let their poverty, stories, and circumstances distract you from that, not for a minute.”